A former hitting coach for the KC Royals also played for the old Kansas City Athletics. Despite playing with the A’s for only one season, he was a fan favorite.

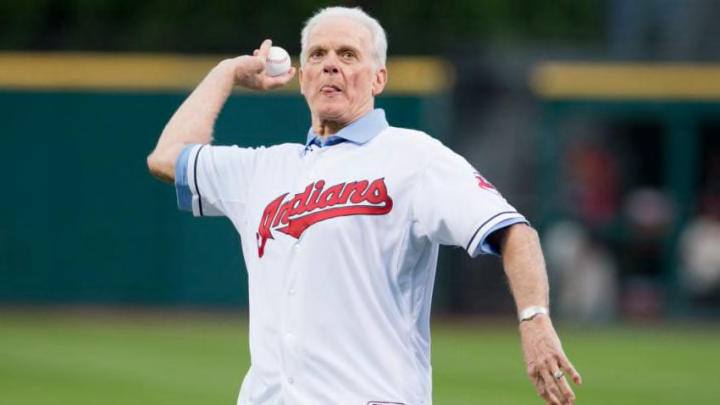

Permit me, if you will, to wax a bit nostalgic about one of the few men to have worn the uniforms of both the KC Royals and their Kansas City big-league predecessors, the Kansas City Athletics. Rocky Colavito, a former Royals coach and A’s player, remains one of the most memorable persons to have graced Kansas City baseball.

If you’ve followed this space for long, you know I was fortunate to spend a few of my childhood years in Lawrence, Kansas, a place so conveniently close to the A’s Municipal Stadium home that I attended more than my share of the team’s games. This gift of proximity allowed me to see many of baseball’s greatest players, including, of course, Mickey Mantle when the Yankees came to town.

Not only did I see Mantle–I actually met The Mick during a game. Understand that visiting teams could access their clubhouse in a way unheard of today, via an open left-field line walkway that led upward toward the park’s main level. Mantle took early leave from the game; I saw him standing alone on the walkway, eating a hot dog and drinking a bottle of pop. (This may have been the exact moment I first realized ballplayers could be just like us).

I summoned all the courage I could and called out to Mantle. To my surprise, he walked over and we spoke for a bit; it was a moment I found incongruent with the accounts of his aloofness I read in later years, but one I still fondly recall.

Mantle was only one of many stars I feel privileged to have seen play–Al Kaline, Jim Palmer, Roger Maris, Brooks Robinson, Whitey Ford, and Frank Robinson, to name just a few. And I even saw Satchel Paige pitch when he joined the A’s for a short time and threw three innings in a 1965 game against the Red Sox.

I considered these players great in their own right, but a young boy just coming to baseball needs a favorite player, and Rocky Colavito was mine. The 1964 season was his only one with the A’s; I was immediately impressed with his demeanor, howitzer arm and dangerous bat. He soon became the player I watched and studied most.

Colavito went about his business on the field in a professional, workmanlike manner, gliding through his pregame work with a smooth, elegant ease that matched the way he ruled Municipal’s emerald right field. Rare was the deep fly or sinking liner that evaded the seemingly effortless pursuit he gave them.

His relationship with fans helped make him the most popular of the ’64 A’s. I met him twice, once at a signing event at Gateway Sporting Goods on The Plaza (a terrific, but sadly long gone place), then on Municipal’s lush field at Camera Day, a promotion probably second in popularity only to Bat Day (in those days, teams gave away real, regulation Louisville Sluggers to the kids, not the miniature, unreasonable facsimiles that replaced them before Bat Days disappeared altogether).

Colavito spent a few minutes with each of the kids standing in the long Gateway line to meet him; he was gracious and friendly as he signed our official American League baseballs, sought our names and answered our questions. He was equally accommodating and friendly when, wearing the Athletics’ unforgettable and famous Kelly Green and gold uniform, he posed with me on Camera Day as my parents snapped away with their cameras.

His throwing arm–that Colavito howitzer–fascinated me; it seemed he could throw out anyone. His accuracy was stunning, his velocity incredible. As a young outfielder (before I turned to pitching, for which I was better suited), I hoped and dreamed my right arm would one day equal Rocky’s. Although I don’t think his velocity quite matches Rocky’s, the KC Royals’ Alex Gordon is probably as accurate; if he isn’t, I’d hate to be a baserunner trying to survive on the difference.

Colavito’s bat stood out as much, if not more, than his arm. A prodigious slugger before he joined the A’s (he hit 268 of his career 374 home runs in the eight seasons before he came to KC, a total including three 40+ homer seasons and a game in which he slugged four) he hit 34 homers for the Athletics and drove in 102 runs. Batting average was the offensive statistic in those days; retrofit contemporary metrics to his ’64 season and you get a .274/.366/.507 slash and a 137 OPS+.

His pre-pitch batter’s box routine was unforgettable. Rocky pointed his bat straight at the pitcher and held it steady before taking his final stance. It was an unforgettable Colavito trademark.

Fans came out to see Colavito hit home runs, a collective quest that intensified as he closed in on 300 career homers late in the ’64 season. Recognizing a great gate draw when he saw it, eccentric but innovative owner Charlie Finley announced he’d present Rocky with 300 silver dollars to commemorate the feat when it was achieved. He parked an armored Brinks truck a few feet beyond the outfield fence; secured inside was a large plaque studded with the 300 promised coins.

But Colavito clubbed the subject home run on the road (collecting his 900th RBI with the same swing); Finley still gave him the plaque when the A’s returned home.

Rocky also made the All-Star team that season; in all, it was an honor he received nine times, including two years when the midseason classic was played twice.

Colavito didn’t bring a pennant to Kansas City–that event would have to wait for the KC Royals–but he brought excitement to town that no other A’s player could. (Reggie Jackson appeared in 35 games in 1967, the A’s last KC season, but it was of little note at the time).

Inexplicably and in defiance of all logic, Finley traded Rocky away just a month before spring training began in ’65. The deal, a complicated three-way transaction between the A’s, White Sox and Indians, returned Colavito to Cleveland, the city that rebelled when the Indians traded him to the Tigers years before. For their part in breaking Kansas City’s baseball heart, the A’s received Jim Landis, Mike Hershberger and Fred Talbot from the Sox. The trade imbalance was striking.

It was the first baseball trade I can recall and it shattered me. In private protest, trying to keep my anguish to myself, I silently threatened to abandon baseball, but by then was too smitten with the game to walk away.

Colavito’s 34 A’s homers were the most he would hit before his career ended with the Yankees in 1968. He did hit 30 in his first season back with Cleveland, but he’d been a professional ballplayer since 1951 and time wasn’t on his side.

But his Kansas City baseball days weren’t over. A friend and former teammate of late KC Royals’ manager Dick Howser, he returned to town as Howser’s 1982 and 1983 hitting coach. It appears to have been a job for which he was well-suited–according to author Mark Sommer in his recent book Rocky Colavito: Cleveland’s Iconic Slugger, Royals George Brett, Hal McRae and John Wathan all praised his work. Coming from Brett, especially, it was high praise indeed.

And if you can access a video of the KC Royals’ famous (or infamous) 1983 Pine Tar Game, you’ll see Colavito in the dugout and on the field after Brett was called out.

Colavito has been out of baseball for some time now; he lives in Pennsylvania with his wife of over 60 years. I understand he lost part of a leg to diabetes but is nevertheless still vibrant at age 86.

This will be my 57th full season following baseball. I’ve seen a lot of players. But Rocky Colavito will always be my favorite.